I have recently read the excellent book Invisible by Philip Ball. It was a fascinating read, packed full of information on myth, magic, philosophy and science. What really struck me was how much science of the 19th century was either driven by, or related to, investigations into the occult. We’re talking about the golden era of seances, mediums, mystics and stage magicians. The great discoveries of the late 19th century: radio waves, x-rays and ‘cathode rays’ (or electrons) all were ‘invisible’, and were often thought to be related to apparent psychic forces, ghosts and other paranormal phenomena.

It’s amazing to look back at it all now with the benefit of hindsight and question how they could have believed this stuff. Particularly interesting was the work of Sir William Crookes, who was either a crank or a dupe (or maybe both, as Ball suggests). This is Crookes, inventor of the famous radiometer, which many will have encountered in secondary school science. It turns out that he invented this device to try measure invisible, psychic forces, and seemed to believe he had been successful.

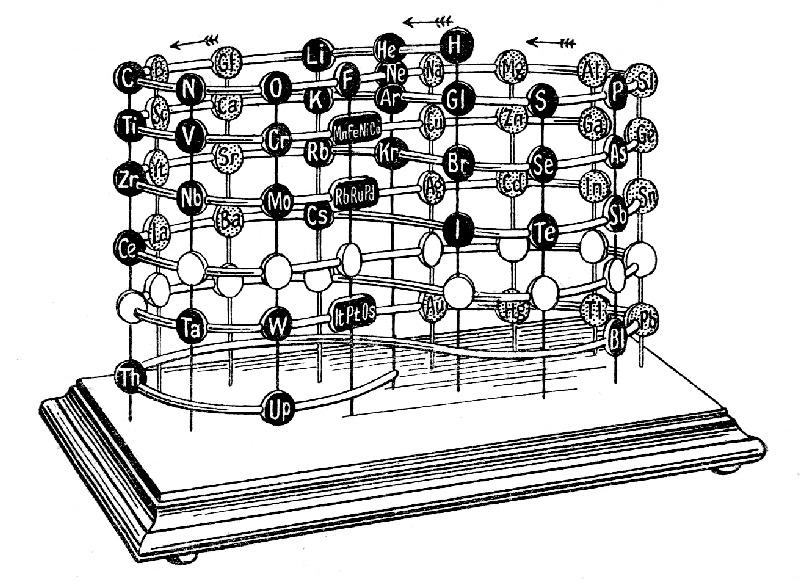

I was pleased to learn about the book pictured here, Occult Chemistry by Annie Beasant and C. W. Leadbeater, two theosophists who basically used their imagination to come up with diagrams of atoms, the structure of which were unknown at the time. In some cases, they came up with structures remarkably similar to the common pictures of atomic orbitals we use nowadays, but they also drew some amazingly complex geometrical shapes that are unlike anything I have seen before. I love that they just assumed they could use their minds to ‘discover’ what atoms looked like! The book also contains a picture of the periodic table from a paper in the Proceedings of the Royal Society, read in 1898 that I quite like:

Invisible really indicates just how well scientific investigations are embedded within the sociological frameworks in which they operate. We like to think of science as being ultra-rational, beyond influence from mere human biases, but despite our best efforts it rarely is. Although the scientific method is designed to avoid such influences, its failure to do so (or the failure of its implementation, more precisely) is something we need to be aware of. I wonder what driving forces and theories for investigations into the ‘invisible’ that science is concerned with now, will look as strange in 100 years as those of Crookes et al. in the late 1800s do today? Many-worlds interpretations? Dark energy? ;)